In Memory of Those I Lost

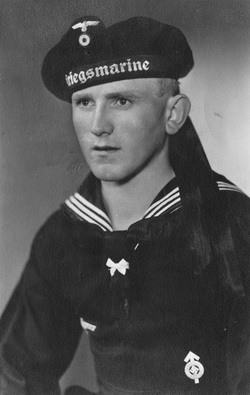

Fritz

My cousin Fritz and I had a special bond. Blond haired and blue eyed, Fritz was the cutest child. We had always been close; he was the big brother I never had. I loved him beyond words. When the war started, Fritz was drafted into the Kriegsmarine, or Navy. He was 19 and assigned to a minesweeper. Because of the war, most of my other male cousins and friends were drafted into the military.

When I was 14, Fritz was approved for leave and he visited us in Berlin for a day before going home to Fellhammer and getting engaged. On his way back, he stayed with us again for one more day. I brought him to the train station. I will never forget our last conversation. My heart broke when he told me that he would not come back alive. I was bowled over by this admission. Preposterous! He was far too young to die.

A few short months later, on July 4, 1944, he went under with his ship after it was hit by a torpedo. He was 21 years old. I still have his very last letter to me, which he wrote from his ship on March 3, 1944.19

When I was 14, Fritz was approved for leave and he visited us in Berlin for a day before going home to Fellhammer and getting engaged. On his way back, he stayed with us again for one more day. I brought him to the train station. I will never forget our last conversation. My heart broke when he told me that he would not come back alive. I was bowled over by this admission. Preposterous! He was far too young to die.

A few short months later, on July 4, 1944, he went under with his ship after it was hit by a torpedo. He was 21 years old. I still have his very last letter to me, which he wrote from his ship on March 3, 1944.19

Lux

Lux and me, ca. 1942.

Realizing just how alone I was in Berlin, my parents were persuaded to get me another dog. By this time, they knew we were allowed to keep a pet in the apartment. I named my fuzzy little pup Lux. Lux was a German Shepherd. He slept with me and for the first time, I felt safe as we snuggled against each other at night. Somehow, he filled the lonely ache in my heart. He grew into an exceptionally intelligent dog. We were inseparable for two years.

One day my parents received a letter in the mail, notifying them that they must take him to a specified military facility to be tested. The German Army was looking through the city's list of registered dogs for German Shepherds that could augment the war effort. If Lux passed the test, the military would confiscate him. I prayed for days he would flunk. I said a hundred prayers to God, promising Him everything and anything if only I could keep my friend. Sometime later, we were informed that Lux had passed. Thank God, I had no idea to what hell he was going.

A letter from his handler came some months later, which explained that Lux had been wounded in the stomach but was expected to make a full recovery. We later received a final letter from the handler, notifying us that Lux had been killed in action on the Russian front. Besides the letter, inside the envelope was a small medal that Lux had been awarded for his bravery; instead of keeping it, his handler had sent it to me.20

One day my parents received a letter in the mail, notifying them that they must take him to a specified military facility to be tested. The German Army was looking through the city's list of registered dogs for German Shepherds that could augment the war effort. If Lux passed the test, the military would confiscate him. I prayed for days he would flunk. I said a hundred prayers to God, promising Him everything and anything if only I could keep my friend. Sometime later, we were informed that Lux had passed. Thank God, I had no idea to what hell he was going.

A letter from his handler came some months later, which explained that Lux had been wounded in the stomach but was expected to make a full recovery. We later received a final letter from the handler, notifying us that Lux had been killed in action on the Russian front. Besides the letter, inside the envelope was a small medal that Lux had been awarded for his bravery; instead of keeping it, his handler had sent it to me.20

Fritz and Heinz

My cousins Fritz (left) and Heinz (right).

My cousins Fritz and Heinz were both killed in 1945, near the end of the war. I have so many fond memories of us all growing up in Fellhammer. The Americans killed my cousin Heinz in Paderborn, a town about 250 miles west of Torgau. Heinz was part of a Panzer tank crew. He and his crew had stopped to relieve themselves when they were all mowed down by a machine gun. His brother, Fritz, who was part of an artillery battery, had already been killed by the advancing Red Army front lines. A rocket-propelled grenade hit the canon he was manning. Shrapnel tore through Fritz’s abdomen in an instant. He lingered for a few days in a field hospital, but eventually succumbed to the devastating wound. Of the four children she had, these were my Aunt Trudel’s only sons. Their sisters, Hilde and Ushie, survived the war. I still miss these two boys dearly.21

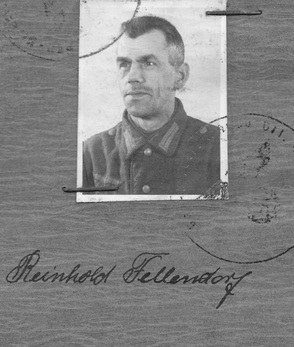

My Beloved Father, Reinhold

A portion of my father's military identification passport.

According to my father's diary, he successfully managed to avoid being captured by the Russians, crossing the Elbe River and surrendering to the Americans at Tangermünde on May 8, 1945. Unfortunately, my father and the rest of the German prisoners in his group were eventually turned over to the Red Army. He was later transported to a gulag in Siberia, but we had no idea what happened to him.

I didn’t even recognize my own father when he was finally repatriated in 1948. While I realize he was extremely lucky to have survived at all, he returned a shadow of his former self. I was consumed with sadness at the sight of him: his hair, only prison camp stubble, was all white; when last I saw him, his hair had been jet black. He was also missing many teeth; when last I saw him, he had a full set of beautiful white teeth. He was all bones and sunken skin now, and his hollow eyes were filled with something that I’d never seen in them before – an uneasy haunted look. My beautiful, strong, and kind father had paid a heavy price fighting a war he did not believe in from the beginning.

My father hardly spoke now; he just sat alone in a chair in our living room, staring into space for hours, tormented by things he kept inside himself, locked away from my mother and me. It was difficult to talk with him. Not long after he got home, he found a job in a bakery. Six months later he became seriously ill. When he developed a high fever, my mother made him stay in bed while she called the doctor. The doctor arrived a short time later, and quickly began examining my father. After taking off his stethoscope, the doctor looked very grim and immediately called an ambulance. His diagnosis: TB. There was no cure if you were a common man; it was a death sentence. My poor father had survived the war only to have contracted the deadly and contagious bacterial infection while in prison.

TB was also known as the “White Plague” or “consumption” because it literally consumed you. If it wasn’t the bloody cough, it was the wasting away of the body that finally killed you. We lost my father little by little. His mind clouded over. When he was still lucid, he would ask my mother, “Who will hang his hat on your bed post when I’m gone?” My mother always replied, “There will be no other after you.” When he died on July 4, 1949, my mother was only 44 years old, and there was no other.22

I didn’t even recognize my own father when he was finally repatriated in 1948. While I realize he was extremely lucky to have survived at all, he returned a shadow of his former self. I was consumed with sadness at the sight of him: his hair, only prison camp stubble, was all white; when last I saw him, his hair had been jet black. He was also missing many teeth; when last I saw him, he had a full set of beautiful white teeth. He was all bones and sunken skin now, and his hollow eyes were filled with something that I’d never seen in them before – an uneasy haunted look. My beautiful, strong, and kind father had paid a heavy price fighting a war he did not believe in from the beginning.

My father hardly spoke now; he just sat alone in a chair in our living room, staring into space for hours, tormented by things he kept inside himself, locked away from my mother and me. It was difficult to talk with him. Not long after he got home, he found a job in a bakery. Six months later he became seriously ill. When he developed a high fever, my mother made him stay in bed while she called the doctor. The doctor arrived a short time later, and quickly began examining my father. After taking off his stethoscope, the doctor looked very grim and immediately called an ambulance. His diagnosis: TB. There was no cure if you were a common man; it was a death sentence. My poor father had survived the war only to have contracted the deadly and contagious bacterial infection while in prison.

TB was also known as the “White Plague” or “consumption” because it literally consumed you. If it wasn’t the bloody cough, it was the wasting away of the body that finally killed you. We lost my father little by little. His mind clouded over. When he was still lucid, he would ask my mother, “Who will hang his hat on your bed post when I’m gone?” My mother always replied, “There will be no other after you.” When he died on July 4, 1949, my mother was only 44 years old, and there was no other.22

|

Click to set custom HTML

|

Popular German War Love Song

The song playing in this video is "Lili Marlene" by Lale Anderson, which was one of Edeltraud's favorite WWII songs and was also a favorite of both German and U.S. troops, especially when sung by German actress Marlene Dietrich. The song is about a soldier going to war, and saying good bye to his sweetheart whose memory helps him to fight on so he can return to her.23

|

|

________________________________________

19 Fellendorf, 153. 20 Ibid., 75-76. 21 Ibid., 171. 22 Ibid., 234-235. 23 "WWII Lili Marleen (1939 Version)," https://youtu.be/4iozcfAeZzE (accessed March 3, 2018). |

|